Back to the black stuff?

“A vinyl recording is probably the closest you can get to hearing what the original artist intended us to hear”

Since 2007 something has been stirring or rather revolving. Vinyl sales having been on the brink of extinction have been steadily climbing. The last time they were this high was 1991 when Simply Red’s Stars was number one in the charts. Vinyl sales still only account for 2.6% of all music sales, but CD and digital download sales are falling rapidly. In 2016 a total of 47.3 million CDs were bought and 18.1 million digital albums bough online, four years ago, that figure was 32.6 million. Consumers of digital music are turning more and more to streaming services rather than opting to own the music outright. In 2016 there were 45 billion audio streams, that’s the equivalent to the UK’s 27 million households each listening to 1,500 over the course of a year.

Whilst digital music is here to stay it’s the resurrection of a format that first appeared in the 1930’s that’s intriguing. I replaced my long-lost turntable 2 years ago and slowly started buying vinyl again. It seems I was not alone. Steve Jobs the late CEO of apple who revolutionised digital music with the iTunes store listened to vinyl at home. In the US sales were up to 13.1 million in 2016 and in the UK, we bought 3.2 million vinyl records in 2016. With David Bowie’s Blackstar being the most popular album bought on vinyl in 2016.

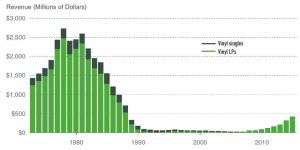

Sales of vinyl in the US: Despite current sales of vinyl being significantly less than in the height of the format’s popularity, the momentum of is building. This growth coupled with decreasing CD and digital music downloads may see the return of vinyl to the mainstream. (SOURCE : Digital Music News)

Is vinyl better than digital music?

My personal answer to this is yes, I hear greater depth and ‘ambience’ in vinyl recordings and whilst the hiss and ‘pops’ were never intended by the musician they do add character to a recording. The technology would also suggest that vinyl has merit.

The ‘A’ side of vinyl

Vinyl is the only medium available today that is fully analogue and fully lossless. The complications of converting digital music is avoided. A vinyl recording is probably the closest you can get to hearing what the original artist intended us to hear.

The compression of digital music for streaming or radio means that the dynamics and textures (the attributes that give recordings their vitality and depth) of tracks are compromised for the sake of ‘loudness’. Vinyl’s volume depends on the lengths of the sides and the depths of the groves. A track mastered for vinyl will have greater dynamism than a digital counterpart but also maintain volume. If a vinyl album is very long it will be quieter. This was one of the reasons that the original vinyl release of Dire Strait’s ‘Brothers in Arms’ was a single album with the last track being shortened, the reissue of the album recently, sees it as a double album with the longer last track now back in place. One of the original producers of the album Neil Dorfsman has been quoted as saying the reissued double album sounds better than the original.

The ‘B’ side of vinyl

New vinyl recordings may not be totally analogue. Some albums have been mastered using a digital recording instead of an analogue source, so the issues created by compression are transcribed across to the vinyl recording. The work around is high definition 24-bit files but even these are a form of compromise.

The Dire Straits example above highlights the issues with trying to fit a hour long album on to one disc, by trying to fit more on grooves get narrower making a quieter recording with more noise. The simple answer is to distribute the recording over many more vinyl discs, something that is happening with remastered originals. Distributing tracks across more discs also mean that the quality loss between the first track and the last on one side of a disc is also alleviated. This quality loss is due to the needle’s speed changing as the circumference shrinks as it gets closer to the centre, causing the needle to lose the ability to follow every millimetre of the grove

Vinyl does have difficulty with high pitched frequencies and sibilance, which cause distortion and crackles, whilst deep bass panned between left and right channels can knock the needle ‘to and fro’.

Finally, there is the pops and hiss which are caused by the lacquer material and the manufacturing process. However, for me these imperfections also generate that warm vibrancy that only a vinyl recording can produce.

The rebirth of the album art form?

With the resurgence of vinyl, the sales of classic albums such as Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Rumours’ or Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ are again on the up, as individuals recreate their original vinyl collection and a new generation of music connoisseurs go in search of legendary albums. It can be argued the advent of digital music destroyed the art of creating an album, with many musicians releasing albums that were merely a collection of prospective singles.

The art work that went into album sleeves for vinyl seemed to carry more significance than modern CD iterations. I struggle to recollect a memorable album cover from the last decade, though that may be also due to my age.

Without doubt the rebirth should be a considered a force for good in a cynical industry, regardless of whether it will improve albums or the artwork that cosset them. 2017 sees the 10 year of National Record Store Day on the 22nd of April. This again is being supported by BBC music and celebrates the UK’s independent record shops. 500 special edition albums will be launched that day.

CNET Photographer Josh Miller takes us on a behind-the-scenes look at the how a vinyl records are made. Experience the record-pressing process from start to finish and enjoy a mellow tune from Tim Bluhm of The Mother Hips. (Copyright: CNET )

- Devon Turnbull’s Ojas Music label launches with...by Fact on February, 2026 at 1:01 pm

An ambient, minimalist EP from members of Balmorhea and Deaf Center. The post Devon Turnbull’s Ojas Music label launches with Muller and Totland’s Unna appeared first on Fact Magazine.

- Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions...by Fact on February, 2026 at 11:15 am

The film's soundtrack features original music by Klein and tracks from Robert Hood, Aphex Twin and Kelsey Lu. The post Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions opens The Underground Cinema at 180 Studios appeared first on Fact Magazine.

- Ryoji Ikeda installation data-cosm [n°1]...by Fact on December, 2025 at 10:23 am

The immersive new work, commissioned by 180 Studios, expands on ideas explored in his acclaimed data-verse project. The post Ryoji Ikeda installation data-cosm [n°1] extended at 180 Studios until 1 February, 2026 appeared first on Fact Magazine.

- 180 Studios presents new Ryoji Ikeda...by Fact on October, 2025 at 1:03 pm

The immersive new work, commissioned by 180 Studios, expands on ideas explored in his acclaimed data-verse project. The post 180 Studios presents new Ryoji Ikeda installation, data-cosm [n°1] appeared first on Fact Magazine.

- Paradigm Shift exhibition at 180 Studios explores...by Fact on October, 2025 at 4:22 pm

Works by Mark Leckey, Andy Warhol and Nan Goldin all feature as part of the major new exhibition. The post Paradigm Shift exhibition at 180 Studios explores revolutions in moving image culture appeared first on Fact Magazine.

- Interview: Gabriel Mosesby Fact on April, 2025 at 3:53 pm

The London artist discusses his ambitious new show Selah and short film, The Last Hour. The post Interview: Gabriel Moses appeared first on Fact Magazine.

![Ryoji Ikeda installation data-cosm [n°1] extended at 180 Studios until 1 February, 2026](https://factmag-images.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/ryoji-ikeda-data-cosm-1-1024x684.webp)

![180 Studios presents new Ryoji Ikeda installation, data-cosm [n°1]](https://factmag-images.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ALubbock_180-14Oct-3554-1024x683.webp)